On a platform situated just outside the Bakehouse Art Complex’s Audrey Love Gallery, artist Amanda Linares presents Between Islands and Peninsulas. The sculptural installation is made up of three separate elements that come together as a table, accompanied by an artist book, that represents her journey from Havana to Miami in 2013. Through the use of text, images, and found objects, Linares reflects on the immigrant experience and explores themes of identity, memory, displacement, absence, and reconnection.

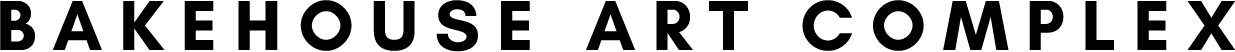

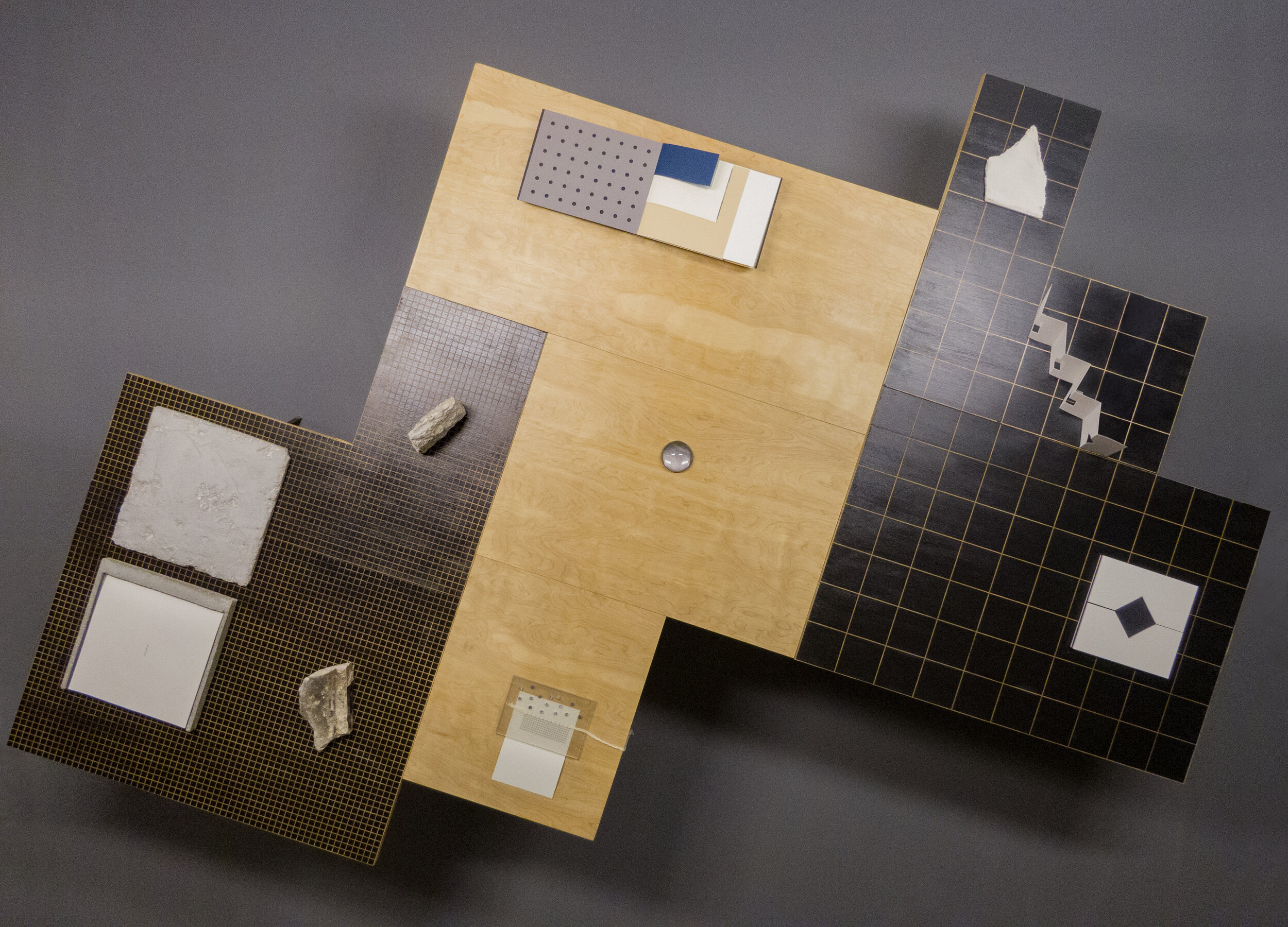

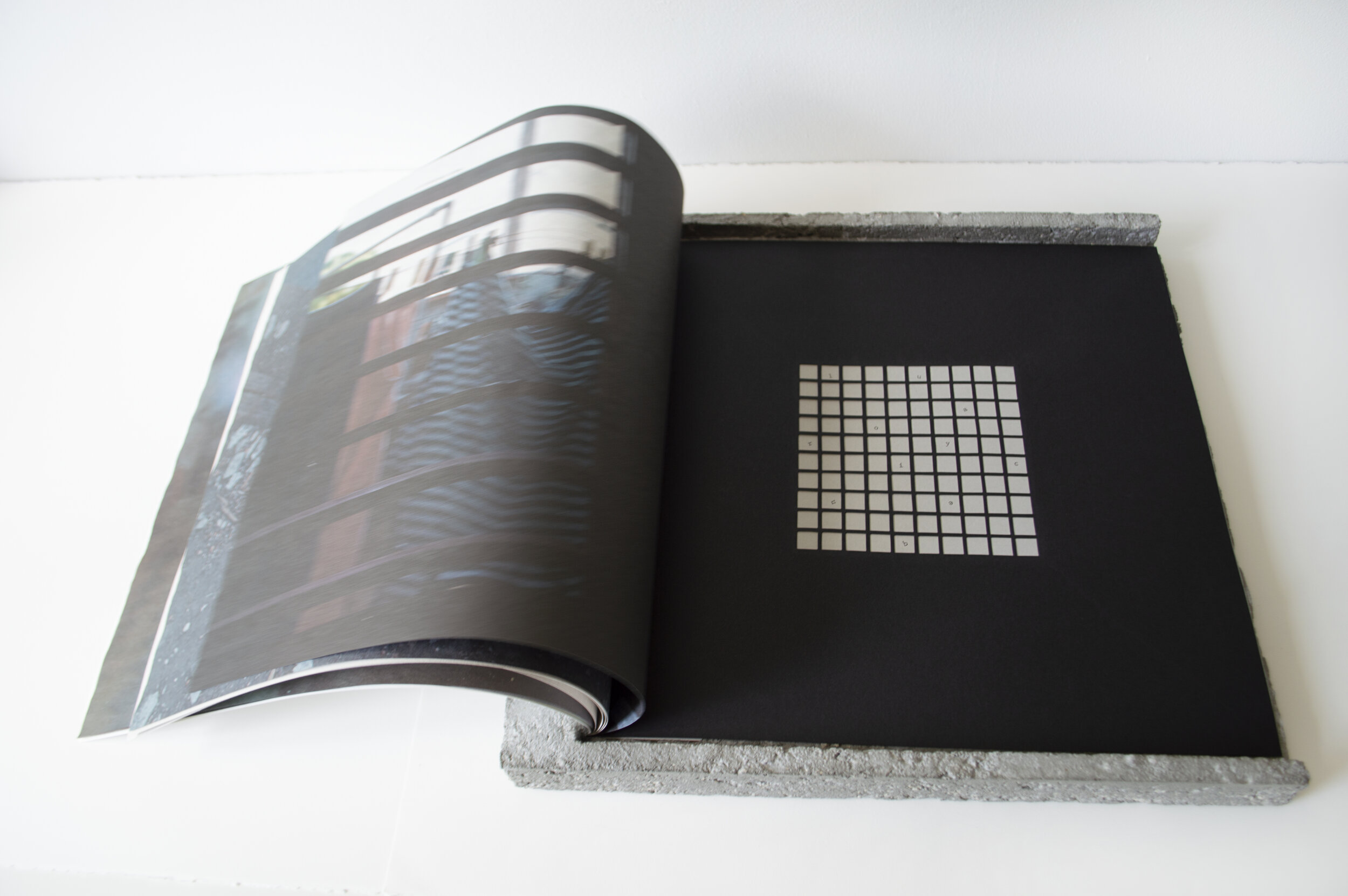

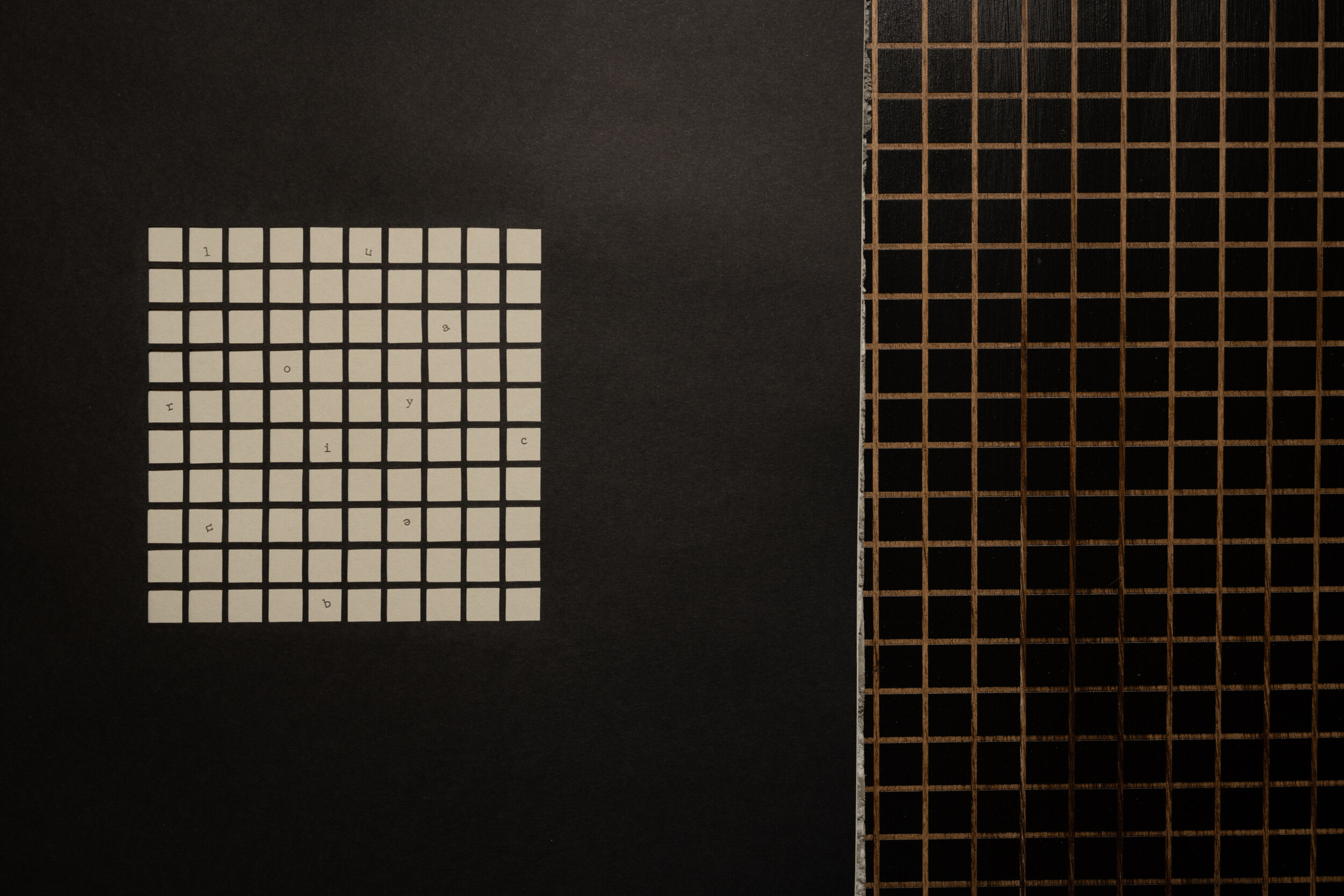

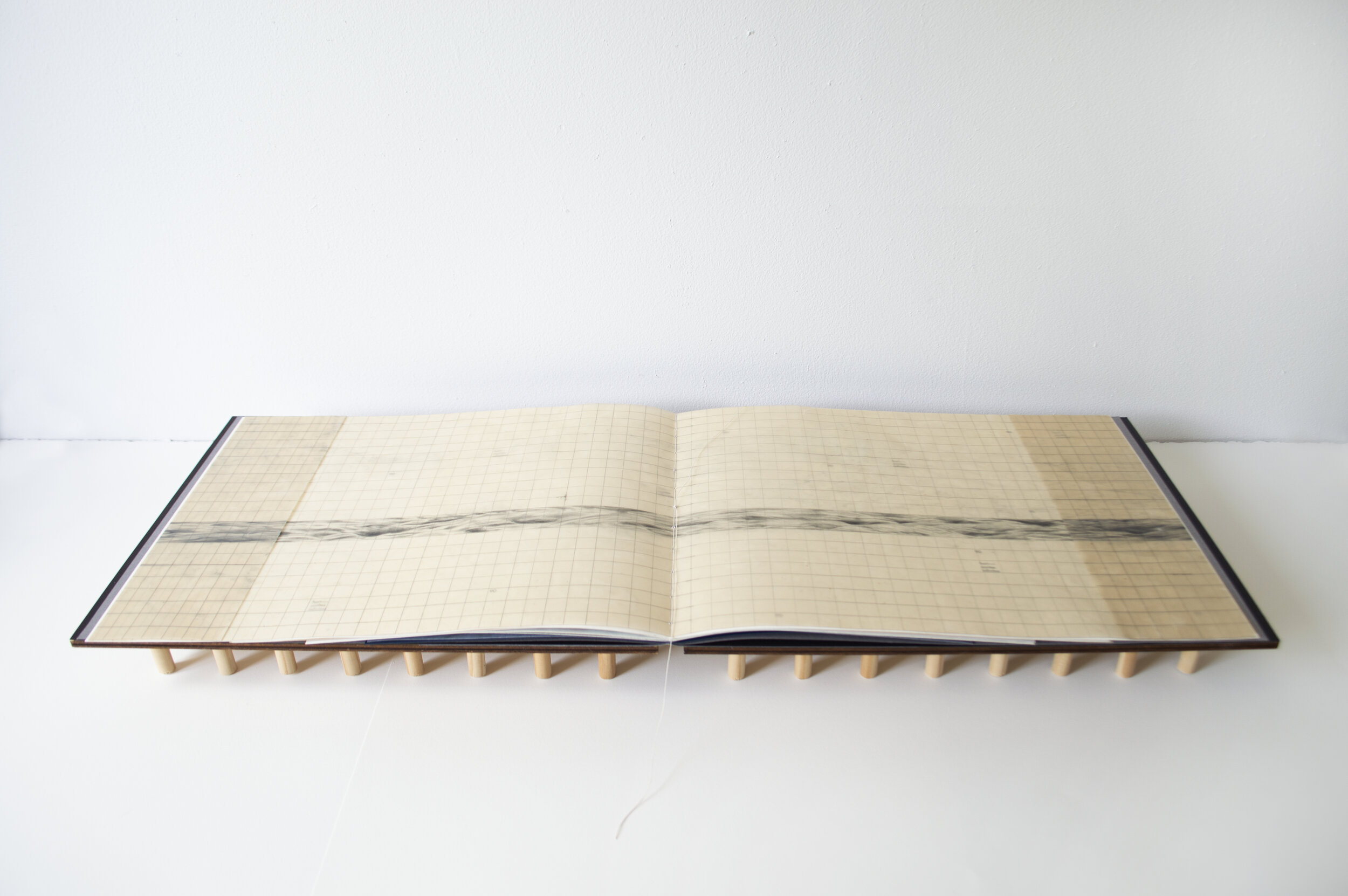

In Between Islands and Peninsulas, three separate elements are installed as one larger table and function as tangible representations of three distinct parts of Linares’ journey: the island of Cuba, the ocean between, and the Florida peninsula. The tables have grid-like patterns the artist utilizes to map the spatial relationships between the different places. The grid becomes a way for Linares to contextualize and organize her personal narrative. On the tables, she places artist books that are chapters of a larger story, like topographical elements in a scattered geography.

The construction and placement of the installation also function to guide the narrative quality of the work. They require the viewer to take an active part by walking around the tables and stopping to navigate the pages of the books. In a way, the viewer is taken on their own journey, mirroring the one Linares represents through her work, an immigrant’s story that transports you over time, space, and destinations.

Linares’ varied use of materials allows her to create works that are simultaneously delicate yet durable. She seeks to capture the contradictions of the human condition through materiality. By using seemingly dissonant mediums in individual works, she is able to convey the coexistence of contradictory feelings and ideas.

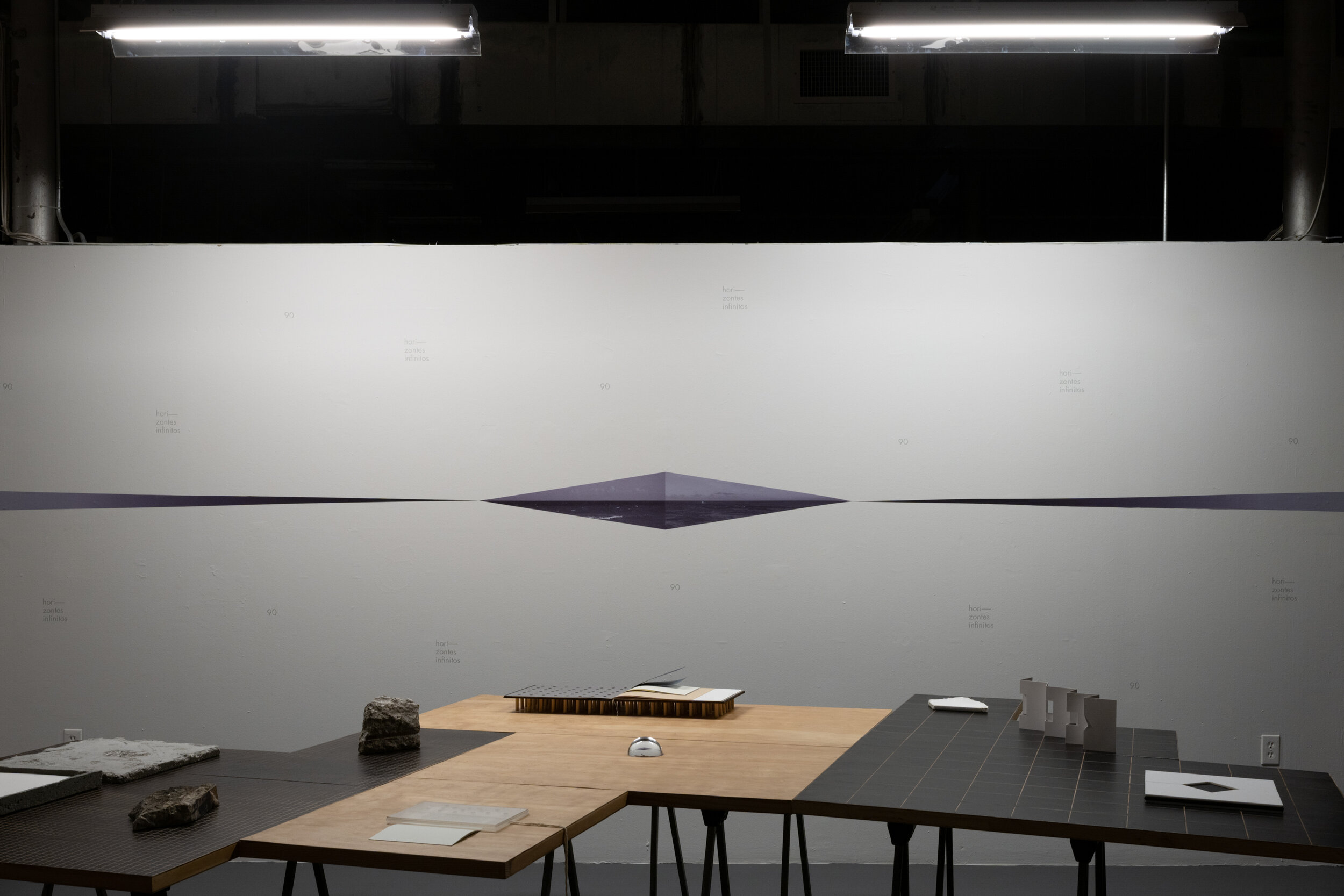

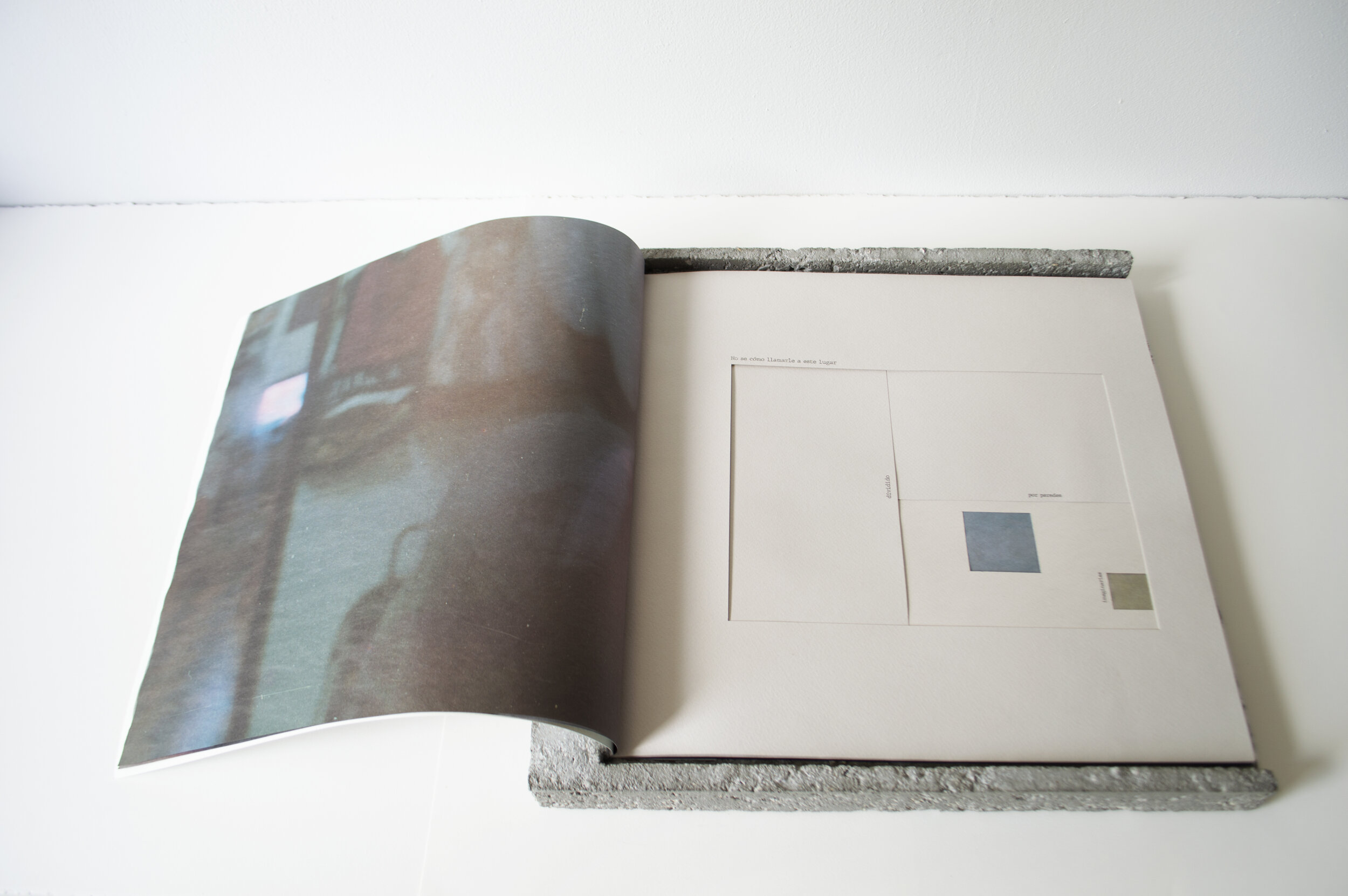

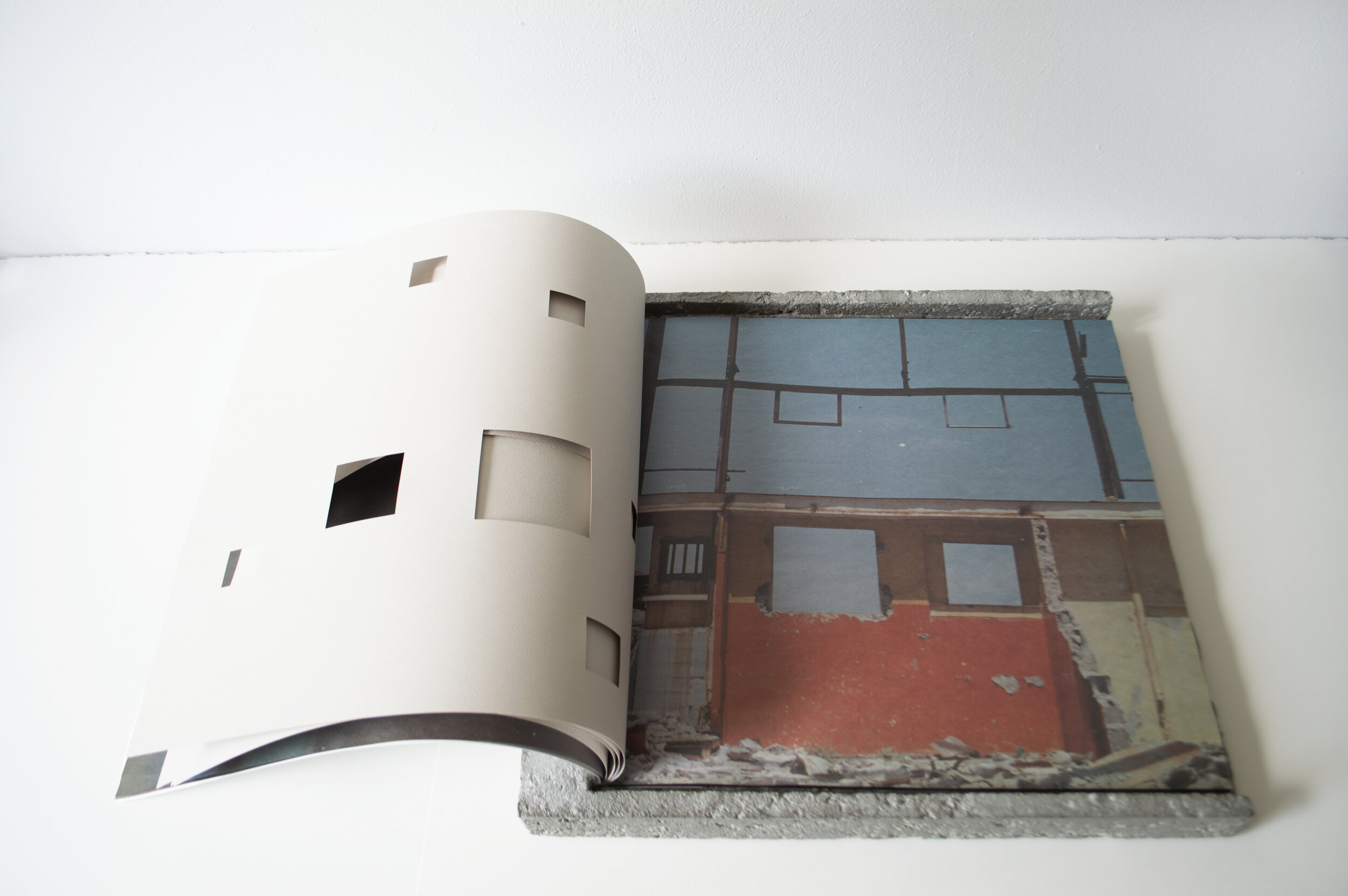

The pages of Linares’ artist book Todo Sigue Igual (“Everything stays the same”) are concealed behind a concrete cover. One must lift the lid with some difficulty to expose its contents, an act which feels eerily similar to opening a tomb. Even then, the pages themselves are difficult to turn and one most hold them down to get through the book. Todo Sigue Igual, which represents the artist’s homeland of Cuba, exudes a heaviness that mirrors feelings of stagnation and pessimism that filled the days of her final year in Havana.

The text, taken from the film Memorias del Subdesarollo (“Memories of Underdevelopment,” 1986) about a man who chooses to stay in Cuba after his wife and friends flee to Miami in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs Invasion, is configured in a way that mimics the film’s fragmented narrative. Like the main character, Linares feels alienated and detached, unable to connect fully to the place she considers home. A single page in the book organizes an excerpt of text into the tight, neat squares of a grid, a visual metaphor for the oppressive socio-political situation that dictates life and living in Cuba.

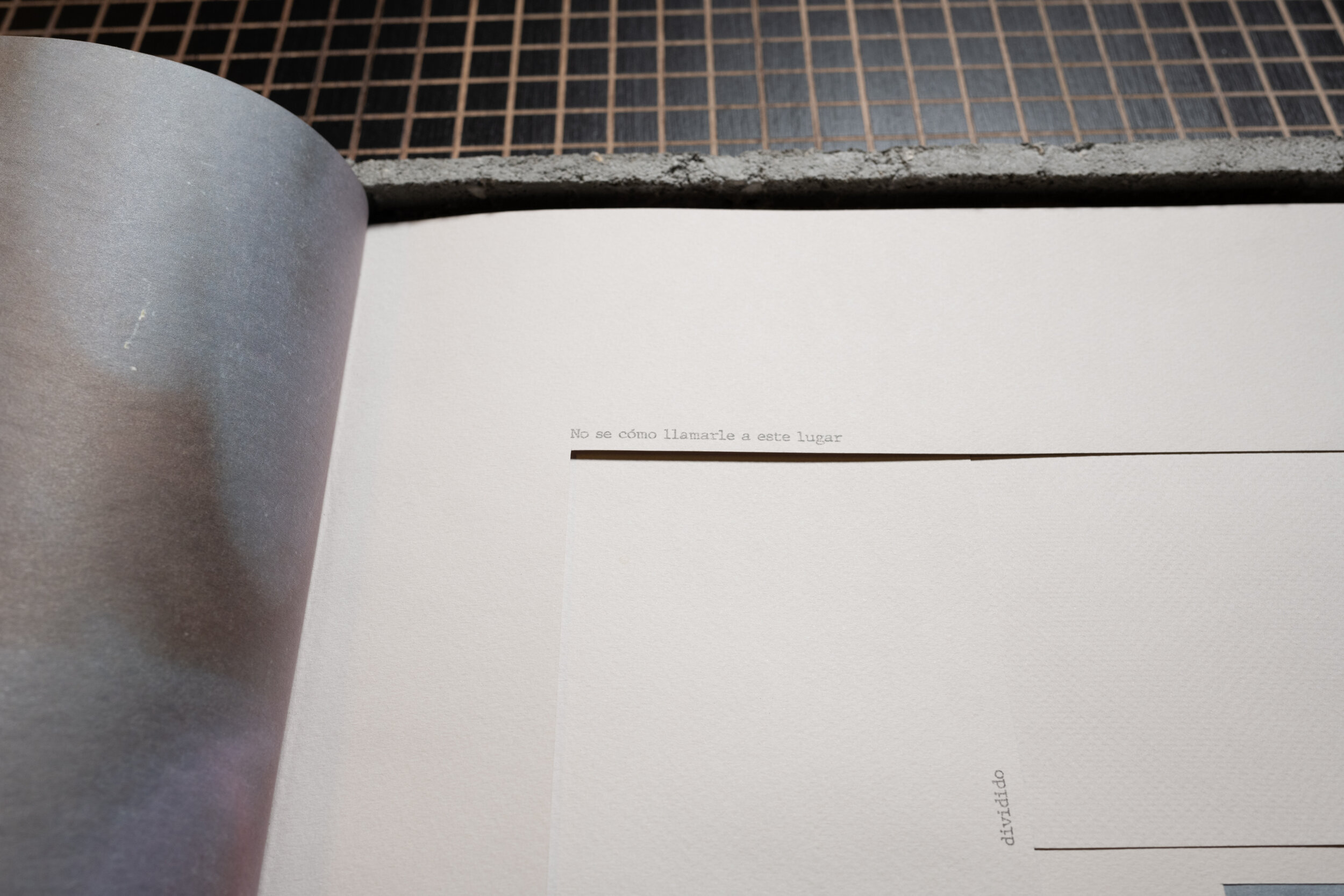

The only line not taken from the film, No se cómo llamarle este lugar dividido por paredes imaginarias (“I don’t know what to call this place divided by imaginary walls”) was a phrase written by the artist’s mother. Linares organizes her mother’s words within rectangular cuts of paper on consecutive pages that, when seen together, reference the floor plan of their house in Havana. Their small, one-bedroom apartment, afforded no privacy, the only window faced a communal hallway, making the thickness and weight of hot, humid summer days barely tolerable.

For the book, the artist searched for old photographs she took when she was still living in Cuba that captured quotidian scenes: laundry hanging on the clothesline, rubble from abandoned buildings in Havana, her mother in the kitchen. The low tonality and textured feel of the newsprint is reminiscent of archival material. Linares, not interested in documenting or presenting information, but rather with conveying particular emotions, selected images that transmit a sense of melancholy and nostalgia.

The way the book is constructed, both in the choice of materials and the ambiguity of the content, adds to the feeling of a story that does not want to give itself away so easily. The final page, which reads ¿Cómo se sale del subdesarollo? (“How do you escape underdevelopment?”), is being consumed by concrete, the rest of the pages illegible, hidden.

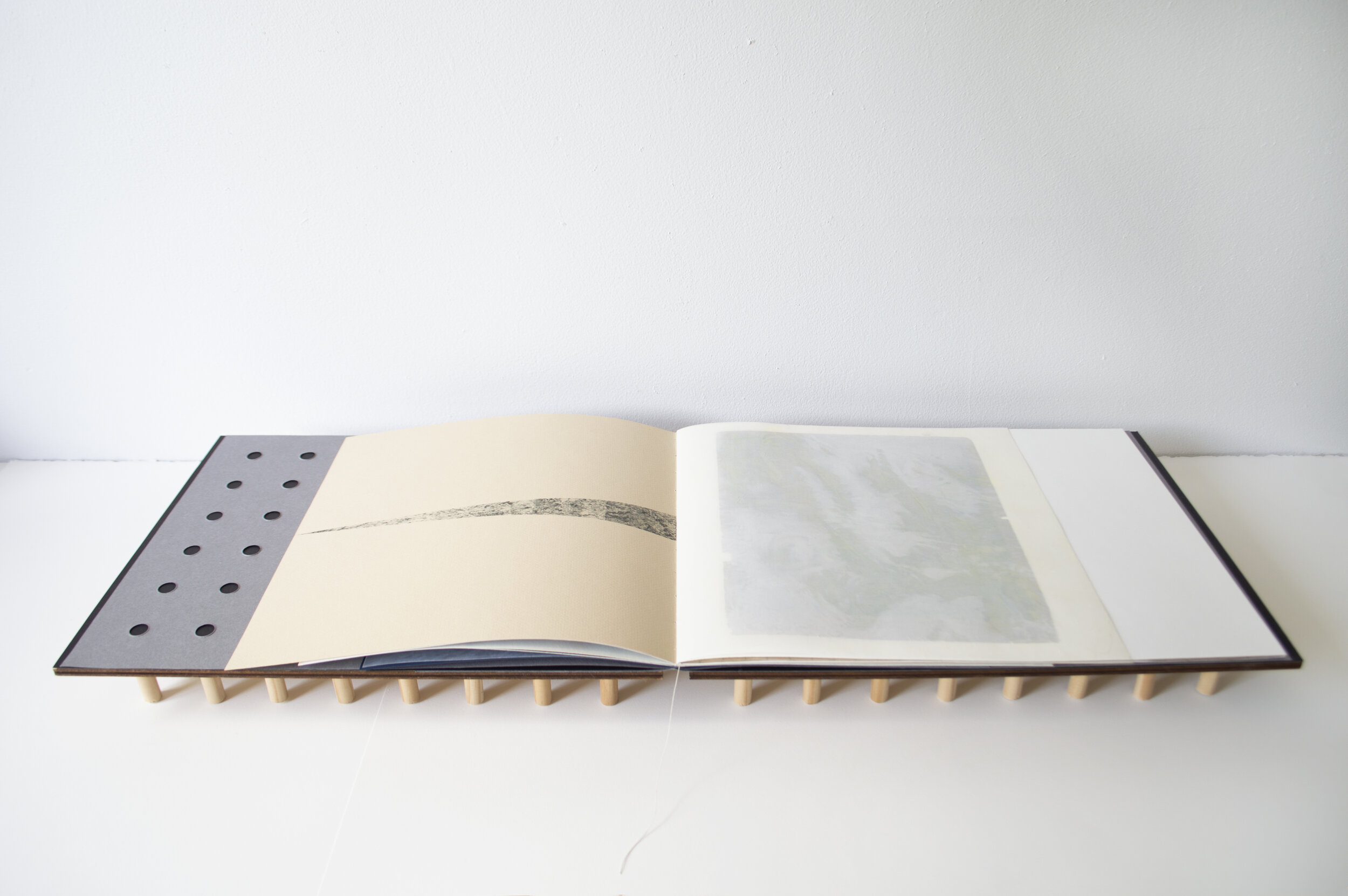

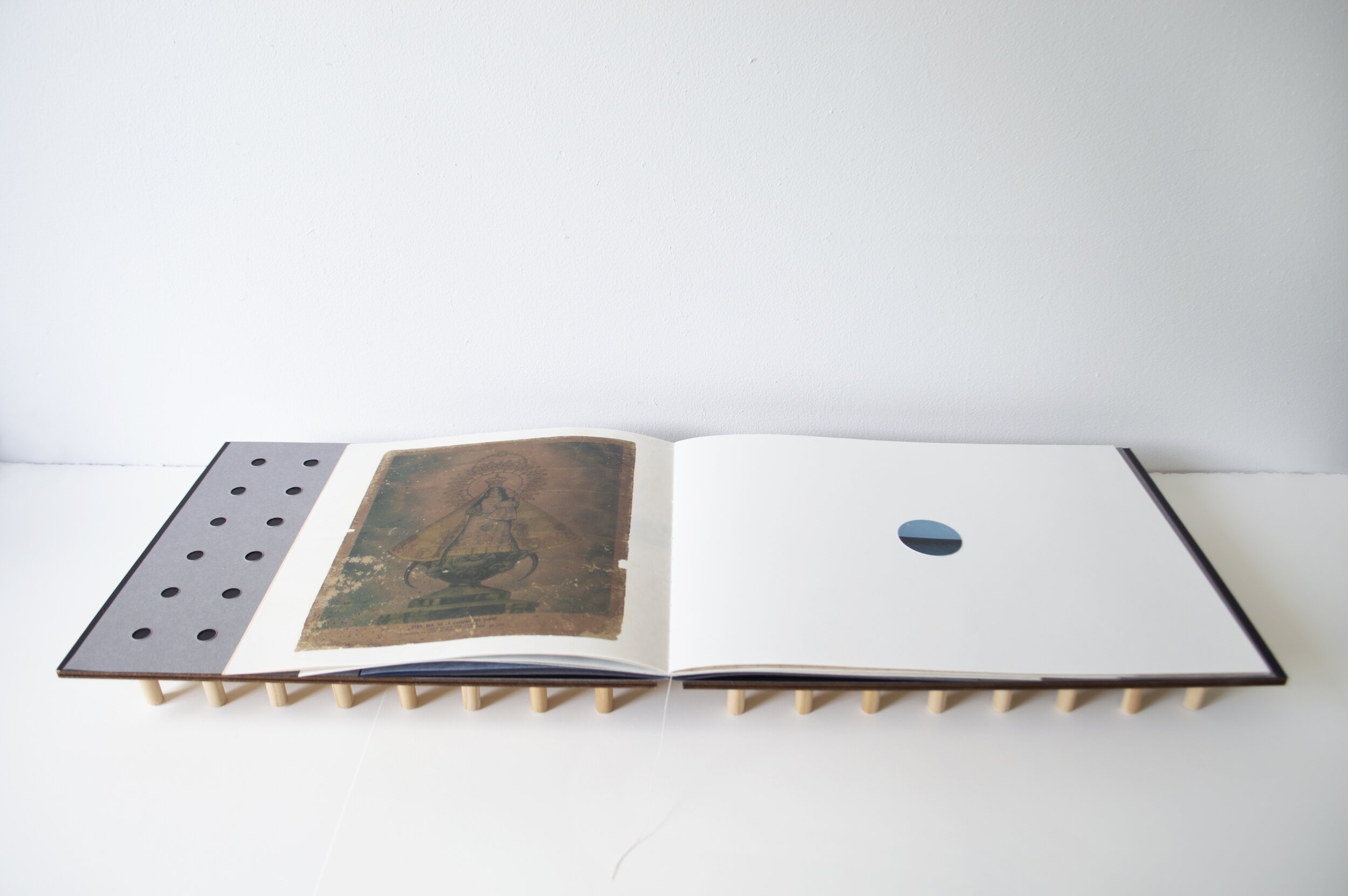

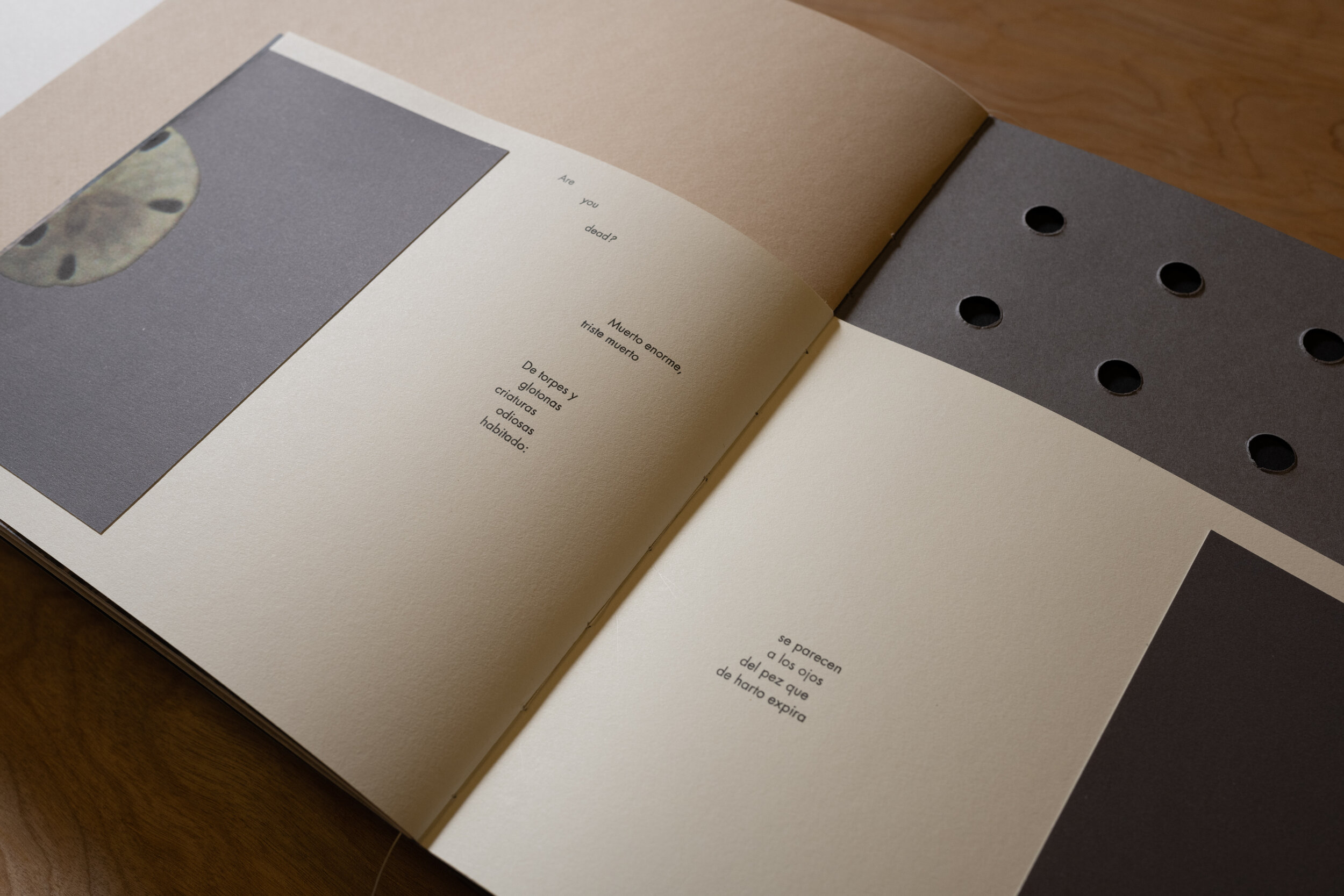

Linares’ second artist book, Agua Salada (“Salt Water”) is about the sea. It has a wooden cover, lined on both sides with small wooden pegs organized in a dot grid system. When opened, it rests slightly elevated on the pegs, as if it were a pier floating in the middle of the ocean. The dot grid, used in the creation of religious manuscripts, alludes to the inmate connection the sea has to religion and spiritual practices in Cuba. Adherents of the Yoruba religion, for example, make offerings to Yemayá, the deity of the ocean, for protection and strength. Within the book, Linares includes an image of Our Lady of Charity, Cuba’s patroness, transferred onto wax paper to reference the candles lit in the offering.

In Agua Salada, Linares explores the sea as a contested site, a place of grief, tragedy, and loss, as much as a place of connection and renewal. In the book, Linares includes lines in Spanish from the poem Odio el mar (“I hate the sea”) by Cuban poet Jose Martí. For Martí, the sea was an enemy, a facilitator of violence, destruction, and submission: I hate the sea, that without anger supports / On its complacent back, the ship / That between music and flower brings a tyrant. Even today, the mere 90 miles separating the island from the Florida peninsula hold a particularly difficult and painful history for Cubans.

Linares also includes text she wrote in English, thereby creating a dialogue between herself and Marti. She reimagines his poem as a conversation, her words posing a question, and his, a response. She asks: Are you dead? He says: ...huge dead, sad dead / Of clumsy and gluttonous creatures / Hateful inhabited. Linares proposes an alternative interpretation of the sea to that of Marti’s: the sea as a connector, rather than a divider. The sea is the in between, the intermediary that encompasses both what she is leaving behind and what she is approaching.

The symmetrical composition of the book also works to express this duality. The pages mirror each other, from small to large to small, building up a sense of anticipation and intensity until one reaches the centerfold, an image of a horizon drawn on wax paper, and from there, the pages diminish again. By incorporating transparent paper and creating small cutouts in a circular pattern, Linares commutes between the hidden and the revealed.

For the artist, the sea presents both a danger and an opportunity. Should one decide to stay or to leave, they must make peace with their choice. Marti reassures her: My sorrows I love, / My sorrows, my shields of nobility...nor that of others / Joy I will poison with my pains. In the end, the sea was her conduit to freedom, a venture towards an infinite horizon, a leap into the unknown.

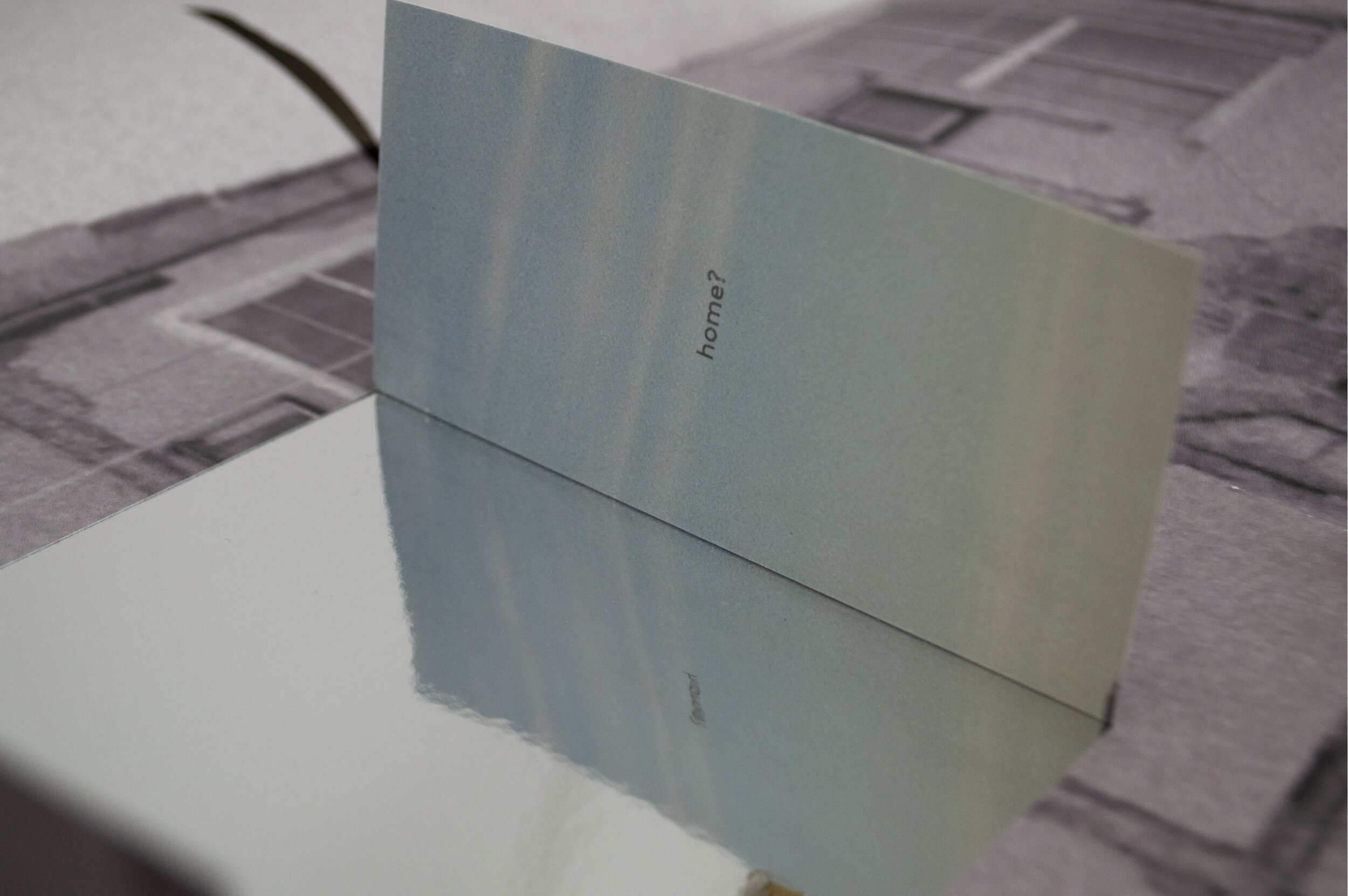

The third book accompanying Linares’ installation, Alternative Realities, is a collection of images reflecting the artist’s first impressions of life in Miami. The cover is made of plexiglass, giving the book a lightweight, synthetic feel. The stark whiteness of the plexiglass, its shine and fabricated newness contrast with the raw decay of Todo Sigue Igual and with the organic quietness of Agua Salada. The cover is a neat disguise for what lies underneath, the magic city facade masquerading less desirable elements. Upon opening the book, one is confronted with the bright red of the inside cover, its intensity starkly noticeable against the muted colors of the images within.

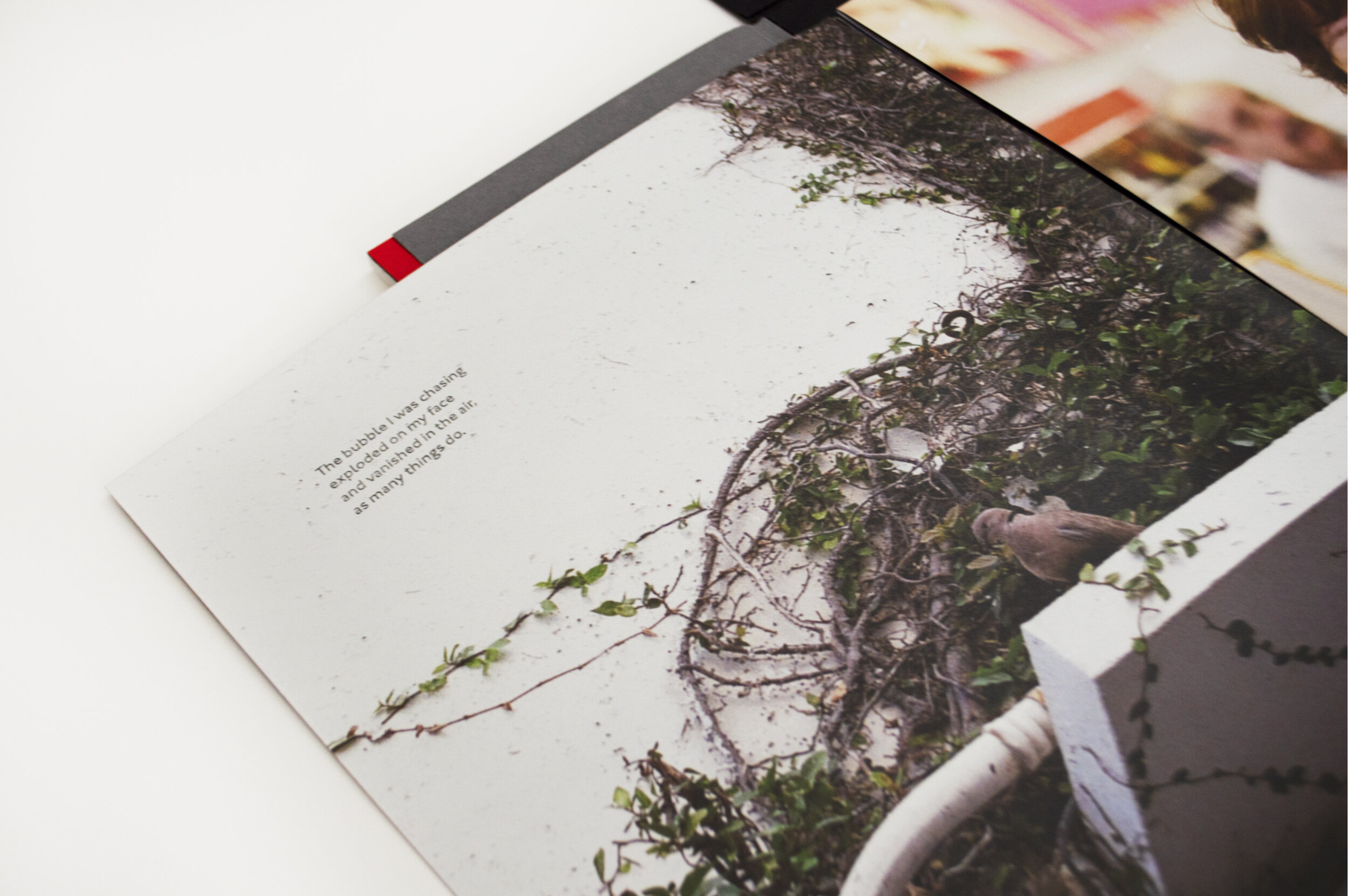

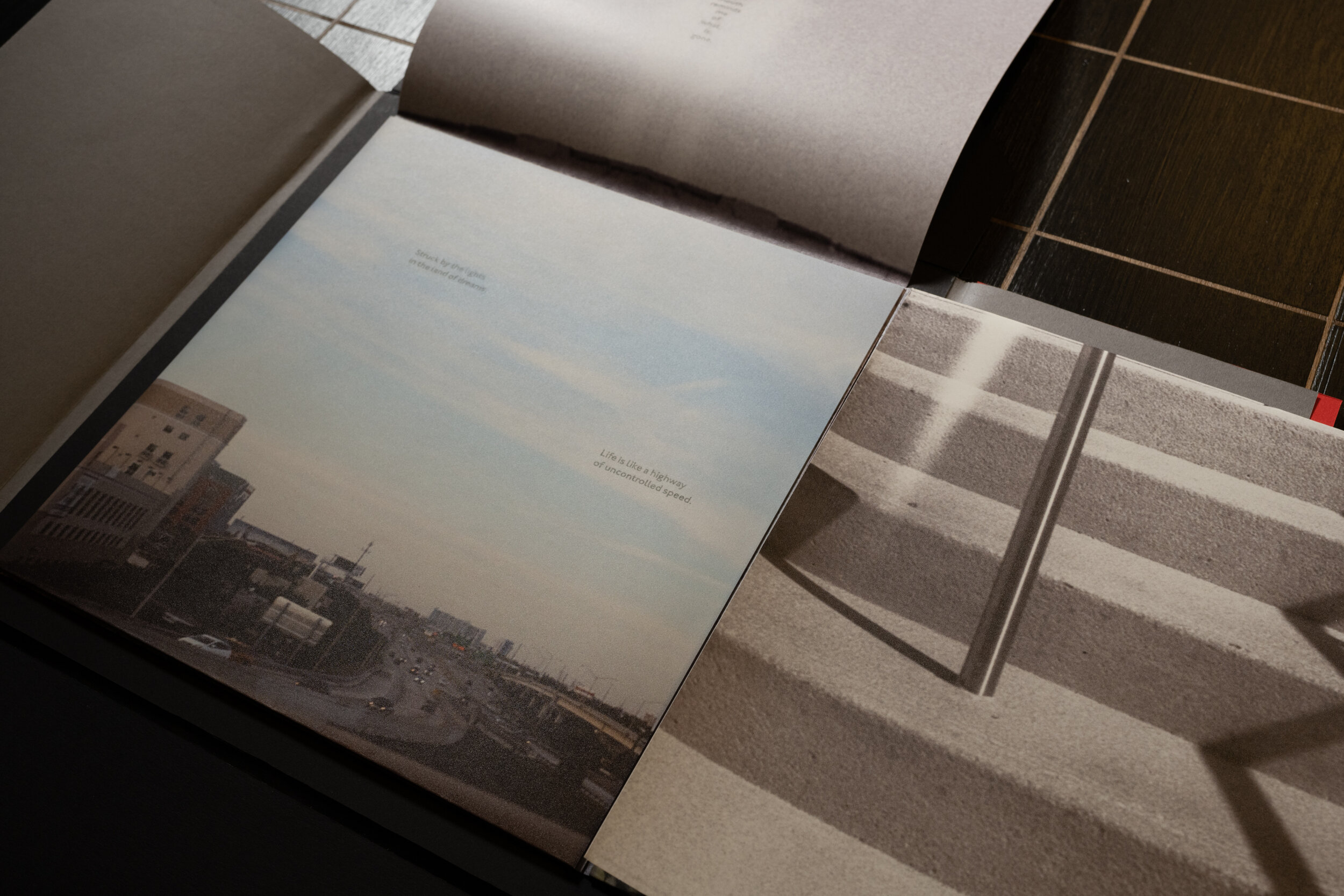

The pages of the book open several times from the center, growing outwards. This new place means freedom -- of thought, but particularly of movement. In one image, a cityscape is crisscrossed by seemingly interminable highways. Written, as if in the clouds, Linares says: Struck by the lights in the land of dreams. Life is like a highway of uncontrolled speed. In Miami, the artist no longer feels constrained as she did in Havana. Her newfound independence and autonomy unfolding before her, expanding like the pages in her book.

And yet, she feels disoriented and lost in the place she does not recognize. The images and the text have a melancholy tone. She writes: Here nothing is permanent. Even though she now lives in Miami, it feels temporary, transient, and fleeting, like the traffic rushing to and from the highway in her photograph. In another page, the words barely visible: While time collapses and expands in this alternate reality, a salty taste in my mouth reminds me of what is gone. The salty taste might reference her recent journey across the sea, but it might also indicate that she has been crying. The book makes apparent the mixed emotions with which the artist is confronting this new life, a longing for what she has left behind, coupled with the relief of having been able to leave.

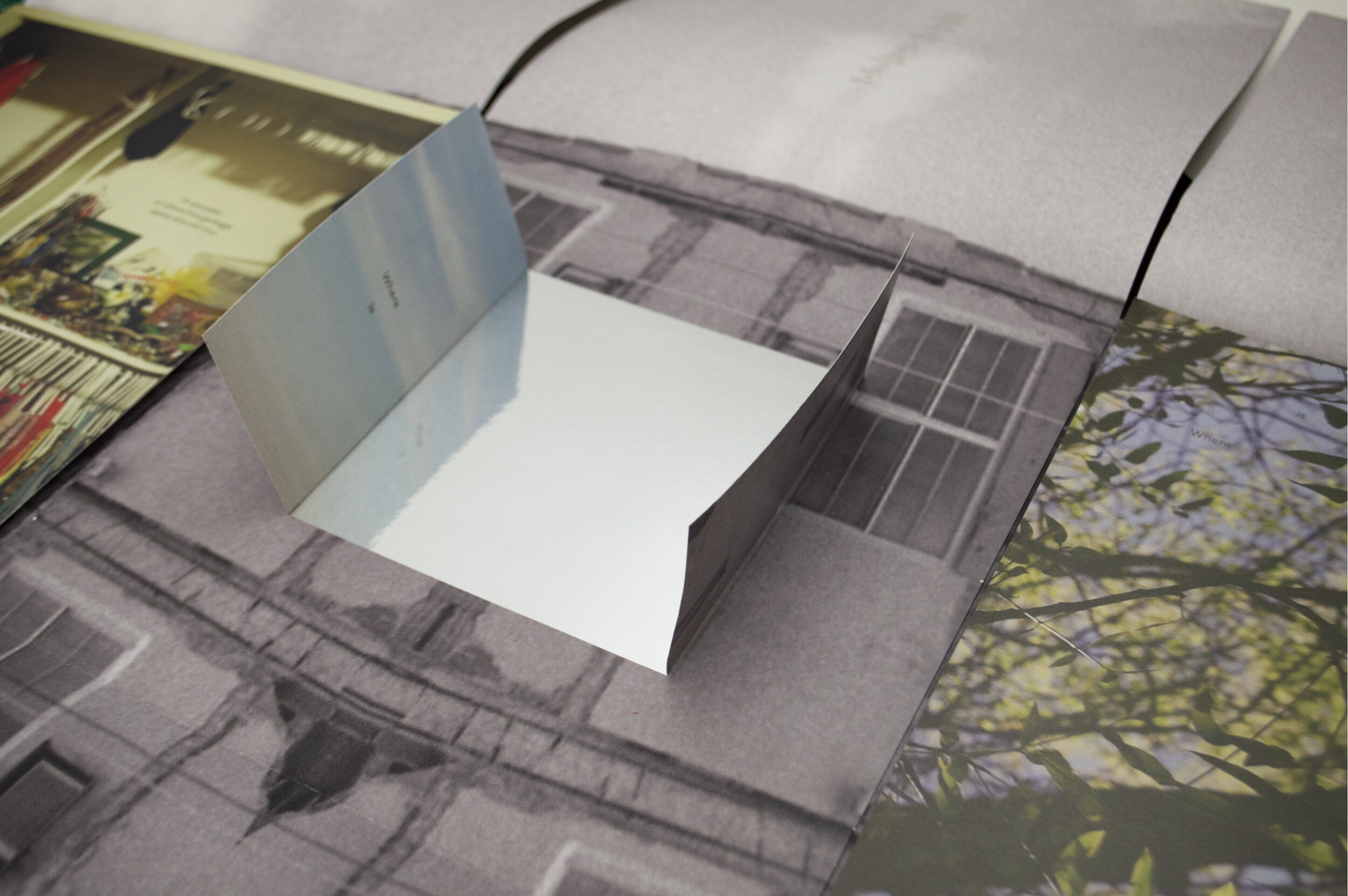

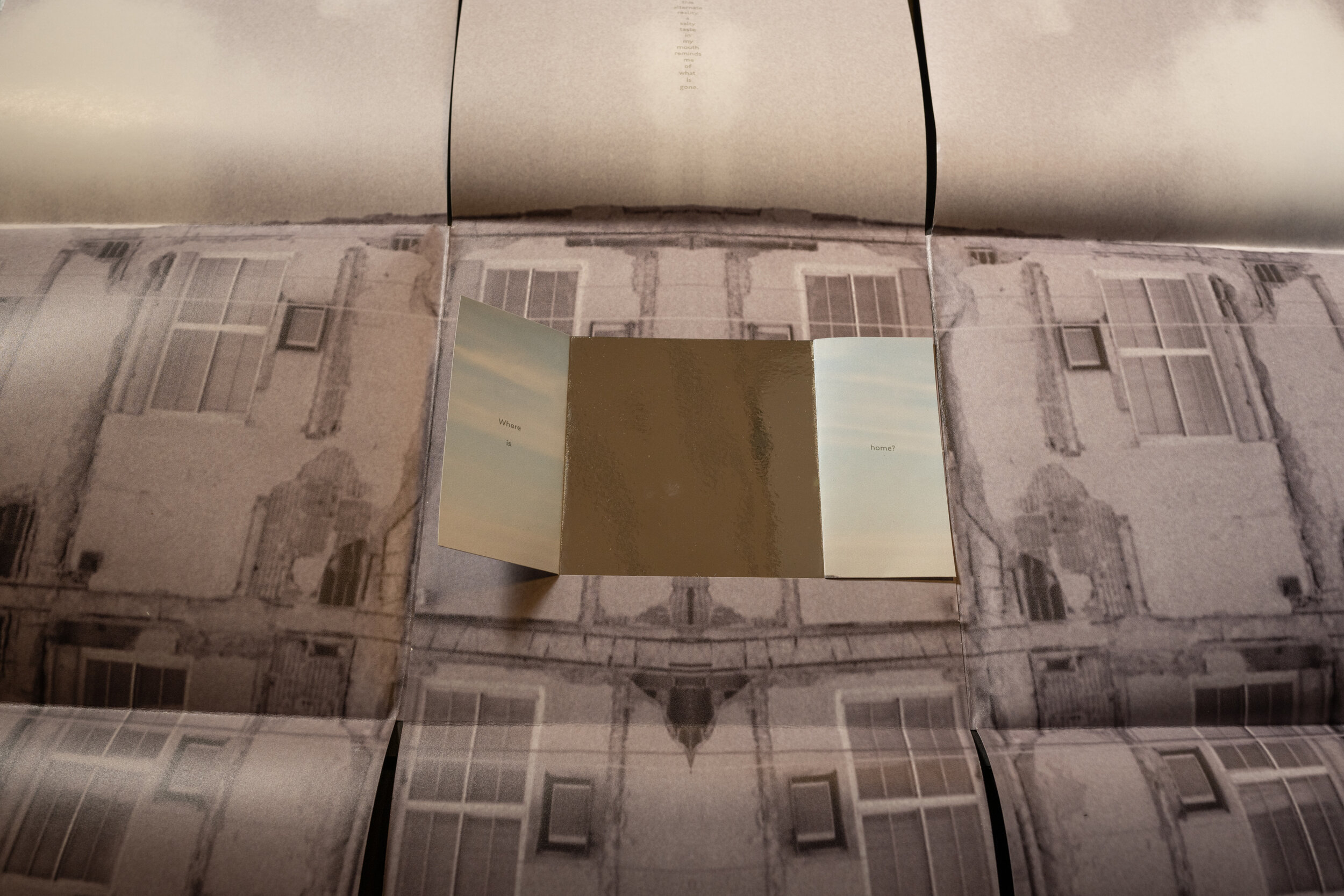

One of the last photographs one sees before the book is fully open is of the now-closed department store, La Epoca, in Downtown Miami. On the facade, the name of the store is flanked by the words Havana and Miami. For a moment, the building could exist in either of these places, different but also so alike. It brings the installation full circle, connecting back to the place where it began. Flipping this page, brings one to the final image, a black and white photograph of a dilapidated building that extends across multiple pages. Barely noticeable flaps are cut into the image. They open up to a mirrored substrate, the flaps on either side like an open window, asking: Where is home?

Text by Laura Novoa, Curatorial + Public Programs Associate

About the Artist

Amanda Linares is a Cuban-born visual artist who currently lives and works in Miami. She first graduated in printmaking from San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba. She recently graduated with a BFA in Graphic Design from New World School of the Arts. Originally, this installation was to be presented as part of the New World’s BFA showcase, which was canceled due to the pandemic.

Linares completed the installation during her participation in Bakehouse’s inaugural Summer Painting Open program, which provided twelve Miami-based artists working in painting and two-dimensional media with free workspace to support their practices for three months from June to September 2020.